The peoples living in what we today know as The People’s Republic of China have been making art for centuries. Our personal archives can hardly hope to present a complete picture of Chinese art history, but we have been graced with some excellent examples of artistic eras and traditions, spanning in some cases thousands of years.

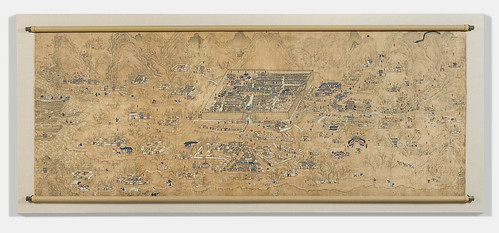

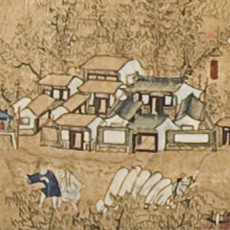

This map, probably from

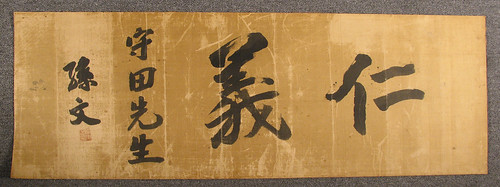

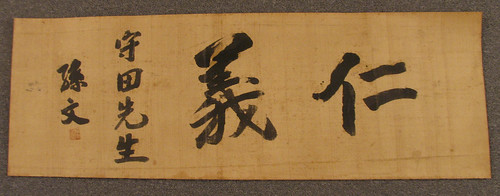

This map, probably from This example of calligraphy is on a silk banner which had deteriorated and become embrittled over time. It had been backed to newspaper at some point in the distant past, which was flaking off in large chunks as it arrived at The Center. Conservators removed the grime and acid burn, and stabilized the fractures in the silk. With the acidic newspaper backing removed, and reinforcement on its tears, this banner will be stable for many years to come.

Terracotta figurines have long been a traditional Chinese art form, especially for inclusion in burials. The Terracotta Army of the First Qin Emperor is the most well known to Westerners who have not studied Chinese art, but the practice extends beyond him and beyond his subject matter. Depending on the prevailing beliefs of the time, important people who could afford it might be buried with objects which would make their afterlives comfortable, or objects which denoted their wealth and status in their past life. Generally these two categories overlapped and horse figurines fit nicely into both, as an expensive but necessary animal to keep. Though some horses have come down to the modern day without their riders, others are known to be ridden by soldiers, polo players, and even an orchestra of musicians. This horse’s conservation process is discussed here: Back in the Race.

Though the rituals and reverence surrounding deceased family members have always existed in Chinese society, the genre of ancestor portraits gained prominence in the mid-fifteenth century. Invariably presented frontally, sitting, with an imperturbable gaze, these commemorative portraits all conform to a type, yet the subject’s individuality is paramount. An incorrect likeness might lead a family to ask blessings of someone else’s ancestor! Thus within the rigid formality of court dress and posture, facial features are a required nonconformity. However, dating these portraits is made difficult by the necessity of a posthumous creation--sometimes even waiting until an ancestor has been reinstated after a fall from grace during his lifetime--and the frequency of copies. Artistically, they cannot be attributed to any sole artist, as they were products of workshops, and the regalia they wear is more attuned to iconography than fashion. These elegant depictions of Chinese royalty and elite are nowadays collected by those who are unrelated to the individual pictured; nevertheless, it is surely a noble gesture that they be treasured and preserved by someone, rather than neglected and left to completely deteriorate.

Though the rituals and reverence surrounding deceased family members have always existed in Chinese society, the genre of ancestor portraits gained prominence in the mid-fifteenth century. Invariably presented frontally, sitting, with an imperturbable gaze, these commemorative portraits all conform to a type, yet the subject’s individuality is paramount. An incorrect likeness might lead a family to ask blessings of someone else’s ancestor! Thus within the rigid formality of court dress and posture, facial features are a required nonconformity. However, dating these portraits is made difficult by the necessity of a posthumous creation--sometimes even waiting until an ancestor has been reinstated after a fall from grace during his lifetime--and the frequency of copies. Artistically, they cannot be attributed to any sole artist, as they were products of workshops, and the regalia they wear is more attuned to iconography than fashion. These elegant depictions of Chinese royalty and elite are nowadays collected by those who are unrelated to the individual pictured; nevertheless, it is surely a noble gesture that they be treasured and preserved by someone, rather than neglected and left to completely deteriorate.

To read the other article written for the "Heritage Artifacts" January Newsletter, please visit: Coverings, Candelabras and Ketubahs.

No comments:

Post a Comment